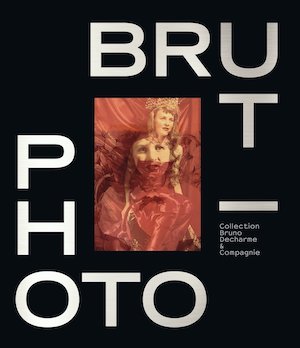

Photo / Brut, by Bruno Decharme and others, Flammarion in collaboration with the American Folk Art Museum, New York, and abcd, Paris, 320 pages, 2020. ISBN: 978-2080204325. Hardcover, $55

Among the varieties of art brut creation, photography has historically received limited attention. A newly extensive, if not definitive, exploration built around the great ABCD art brut collection of Bruno Decharme takes some steps to remedy that situation.

Photo / Brut, the exhibit and catalog, boasts impressive scale, and Decharme’s deep art brut experience gives him standing to help define what art brut photography might mean. That’s not exactly what this project seems to be about, however, with the connection to photography a bit loose at times. It encompasses not only actual photographers but also artists like Charles Dellschau and Henry Darger, who incorporated printed images into their work. Even more of a stretch are those who simply used photographs as source material. Together, these kinds of artists constitute about half of Photo / Brut’s roster.

As a result, this is less a survey of self-taught photography than a story about how art brut creators respond to and use mechanically reproduced images. As such, it can illuminate the relationship between art brut and the surrounding culture, even if it sheds less light on photography per se than one might have hoped. (The curators, of course, have every right to tell the tale that most interests them.)

So, if an artist like Adolf Wölfli with his collaged-in printed images is clearly in the art brut canon, where on the continuum do these other artists lie, given the cultural engagement implied by the use of printed images? Is there a difference between being fully raw versus just somewhat on the margins of the surrounding culture?

And what of the artists who take their own pictures? Besides the fact that they are working with a sophisticated type of cultural technology, what makes their practice more akin to art brut than to the work of vernacular picture takers, who are engaged in something more like a folk craft?

Introducing a chapter devoted to works that interrogate identity, Brian Wallis writes, “These outsider artists using photography were less deviants and social outcasts than amateurs, cleverly adapting various forms of vernacular photography and mass media collage to express their private ideas about gender and sexuality.”

Camille Paulhan in her essay struggles with the brutness of the work, but concludes, in part, that the “freedom” with which these artists use photos—“without obsequiousness”—moves their work beyond the cultural conventions around photography. That could seem to be a brutish direction, though it’s easy enough to remark that plenty of non-brut artists also use photography (and other source materials) without obsequiousness and without much regard to cultural conventions.

The leap from merely vernacular to art brut is in the content, it seems, and in the “cleverness” with which the leap is made (and perhaps the obsessiveness). But how truly liberated from cultural norms can the art be under these conditions? After so many years of photography being ubiquitous, cultural sophistication about the power of its images is also ubiquitous, even among art brut creators.

This is a case where it doesn’t much help to look for guidance to art brut’s definer, Jean Dubuffet. “During Dubuffet’s period collecting from 1945 to the late 1960s, photography was still seeking legitimacy as fine art; therefore, the inventor of art brut’s ‘anti-academic’ offensive did not target it,” Decharme points out. That is, since it wasn’t relevant to his war on the establishment art world, it didn’t much inform his thinking.

It seems inevitable, though, that photography would capture the attention of art brut creators, if not Dubuffet, and, thus, eventually enter the canon. Some embraced photography as part of a project of obsessive documentation, whether Eugene Von Bruenchenhein with his thousands of pictures of Marie, “Type 42” and his or her images photographed from a TV set, or Miroslav Tichý and his voyeuristic recording of his community.

In some cases the individual photos are prosaic; it’s in obsessive quantity that a compelling vision coalesces. That might include Horst Ademeit’s thousands of annotated Polaroids demonstrating the deleterious presence of “cold rays” and Elisabeth Van Vyve’s account of her lived environment. Her pictures are fascinating mostly because of the details she exhaustively documented for 30 years.

Sometimes other things besides vision coalesce, however—obsessions that are more unhealthy than interesting or ideas that are just plain unpleasant. The Ademeit Polaroids seem to cry out mental illness, with photography making art brut’s sometimes-discomfiting embrace of that particular pain seem more tangible than it might be in a painting or drawing.

What considerations of ethics and taste apply for Marian Henel’s amateurish photos of dolls in apparently sexual poses and his cross-dressing self-portraits in similarly suggestive positions?

“He was very short, obese, and afflicted with grimaces that he could not control,” says the catalog. Although his body of work might be seen as constituting performance and, thus, deserving of artistic recognition, some performances might be better unseen.

It is admirable that the curators are not afraid to show challenging work, but being challenging doesn’t inevitably mean good. By bringing the viewer face to face with a creator’s pain, some of this work can surface misgivings about collection and curation practices that valorize mental illness.

Yet even if there can be discomfort with some of this work, in only a few cases does the art seem overshadowed by the pain. Even where the artist’s pain is evident, we needn’t dismiss the art because the artist was in pain, though we also shouldn’t dismiss its relevance to our response.

In any case, the best of the work on display here is stunning.

Among the less familiar material in Photo / Brut (to me, anyway), Elke Tangeten’s embroideries on printed images were a revelation. Pepe Gaitán’s work is very strange but also very cool. He photocopies printed pages then inks over most of the letters so they look like abstract symbols, and he collages in images. Leopold Strobl starts with printed images but then draws over them, so that little of the original photo remains visible. The results are evocative and haunting.

Besides the already-mentioned Von Bruenchenhein, Darger and Dellschau, Photo / Brut includes a number of other well-known artists who created or used photos and printed images in their work, including Morton Bartlett, Steve Ashby and Lee Godie, among others.

As is happened, those same artists figured in at least two previous exhibits devoted to “outsider photography.” The first was a 2002 show at Intuit, Identity and Desire, curated by David Syrek and Jessica Moss, which featured Godie, Bartlett and Von Bruenchenhein. The second, 2004’s Create and Be Recognized, curated by John Turner and Deborah Klockho, toured after originating at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco (and to which, full disclosure, I was a lender). Both shows investigated what art brut or outsider photography might actually be. No less an authority than the late Roger Cardinal wrestled with that question in a Create and Be Recognized catalog essay.

The Intuit show is unmentioned in the Photo / Brut catalog, and, although Decharme takes note of Create and Be Recognized, he more or less dismisses it as concerning mostly “folk and vernacular photographs.” That’s a bit odd given Cardinal’s essay and the fact that more than half its 18 artists are featured among Photo / Brut’s 50-plus creators (and the rest might as well have been). In other words, it’s a stretch to claim that “this international-scale exhibition [is] the first on the subject of art brut photography…” as the Photo / Brut curators do in the foreword.

For his part, Cardinal worked hard to distinguish art brut from vernacular photography, though not with total success. Exploration of that frontier remains a task to be completed. If “taking photographs represents one of the main cultural skills of this century,” as Cardinal quotes Joachim Schmid in his Create and Be Recognized essay, then it should be no surprise that self-taught artists would avail themselves of its creative possibilities. For Cardinal, the key question was how a given artist pushed the medium beyond its vernacular language to something particular and highly personal.

With a few exceptions, most of the artists in Photo / Brut do so, which means it fulfills, to some extent, Cardinal’s hope that what he called a scarcity of “authentic representations of outsider photography” might just have been a temporary condition. “We have not yet scanned the field with a proper idea of what it is we are looking for,” he wrote.

Although Photo / Brut has neither exhausted the hunt nor answered the biggest questions, it certainly extends our knowledge.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.