|

J.B. Murray: Reading Meaning

It can't be easy to write a book about an artist whose work is as inherently cryptic as J.B. Murray's. His voluminous script reflected his inability to read or write. His drawings edge toward an abstraction that is almost as hard to explicate. His use of a jar of water to help decipher the writing supplies a twist of the bizarre. In the 10 years late in life that he made art, Murray joined the ranks of American outsider masters with a large body of work created under orders from God and displaying a distinctive formal complexity. Mary Padgelek does what she can to explain it in this modest but readable book. Although she never met Murray, she had access to his neighbors and collectors, as well as to videotaped interviews. Most important, she takes Murray seriously, exploring his religious context in some depth, giving him the benefit of the doubt when it comes to interpretation of the work. That means she typically favors his explanations when they are available. However, they aren't always available. And like so many writers on visionary and self-taught art, Padgelek, an artist and art Ph.D., ends up reading meaning into work in the absence of evidence, and confusing analogy with explanation. This practice seems especially prevalent -- almost automatic -- when the subject is a southern black artist and the writer is interested in African connections. There are certainly religious and cultural practices that can plausibly be related to African antecedents, and some of those practices plausibly influenced Murray's art. For example, Padgelek points out the African roots of the folk tradition of conjure and relates it to Murray's own understanding of the world. "Conjure and hoodoo constituted the spiritual entities he fearfully respected but did not practice himself. Murray often called on Jesus to protect him from the conjure of those he believed wished him harm," she writes. But tracing African influence on actual southern Black culture and then showing how that culture formed an artist is nothing like the leap required to relate a superficial resemblance between Murray's script and Arabic with spotty evidence that some early 19th Century slaves (not in Murray's Glascock County, GA, locale) were Arabic-speaking Muslims. As her citations show, Padgelek is not alone in elevating resemblance into causality. She quotes one writer who finds it significant that water is commonly a part of divination processes in West Africa, and she references Robert Farris Thompson's notation of a similarity between Murray's work and the spirit writing of a contemporary African. While Africanisms may be intriguing, other roots are far more usefully established. A good example is the parallel between Murray's script, which he readily translated into English, and Christian glossolalia, for which there also is a gift of translation. Speaking in tongues is a much more compelling analog in this case than African spiritual practices, present or past. To her credit, Padgelek's analysis of Murray's religion goes beyond just seeking influences. By considering his success as an evangelist, she raises an issue equally applicable to Howard Finster and a host of other self-taught artists who preach through their work, mostly to an audience of non-co-religionist collectors and casual purchasers of what many undoubtedly see as quaint southernisms. In this she is sensitive to Murray's religious intent, which is refreshing. She also makes a case that in some sense his evangelism was successful, if only in bearing witness to the force of the Holy Spirit and to his obedience to God's direction. Evangelism, she points out, is not necessarily a matter of notches in a Bible representing individual saved souls. Padgelek does not fully explore the paradox of collectors living with work whose deepest messages could not be more challenging or more downbeat. Her explications of Murray's paintings, with their ghostly crowds of lost souls, pose the question of just how charming they can be if really understood. Are you fully appreciating his art if you're not taking their warnings of damnation as seriously as he did? She also could have spent more time considering how collectors affected the artist and his work. She mentions that his use of water to translate his script became more ritualistic as more people visited, and she notes that his work became more densely filled with figures when collectors started supplying poster board and larger surfaces. But mostly she merely repeats the claim that the attention influenced the quantity of his output, not its character. The story also could have benefited from a longer account of how the surrounding community received such an enigmatic visionary as Murray, and how his artistic success might have affected his neighbors' perceptions. While arguing that Black fundamentalist culture is less dogmatic than its white counterpart, and thus more tolerant of Murray's eccentric art, she establishes elsewhere that he still raised eyebrows in his church. Yet she does not really follow up on this point. Despite these flaws, the book adds useful information and analysis to the J.B. Murray story, offering more depth and much less condescension than the biographic capsules that are the usual fate of outsider artists. Most unfortunate is the poor quality of the reproductions. That's no surprise for what is basically an academic monograph from a university press, but it hardly helps the cause that half the supposedly color plates aren't, and that many of the black-and-white images are illegible. As a result, the book is not the complete introduction to Murray and his art that it could have been. If you already own the mammothly illustrated Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art, you may find it helpful to keep the section on Murray handy as you read Padgelek's study. This review originally appeared in The Outsider, the magazine of Intuit: The Center for Outsider and Intuitive Art. |

The Latest Stuff | Roadside art | Outsider pages | The idea barn | About | Home

Copyright Interesting Ideas 2001

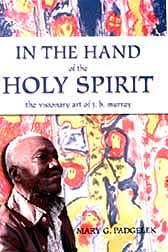

In the Hand of the Holy Spirit: The Visionary Art of J.B. Murray

In the Hand of the Holy Spirit: The Visionary Art of J.B. Murray