Does it matter that the history found in most Hollywood films based on real events and real people is ersatz? Watching 2020’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 and its frequent falsifications, I was reminded of a piece I wrote years ago about how a fake cinematic reality can all too easily substitute for actual historical knowledge.

Hollywood producers certainly have the artistic prerogative to not care about rendering an accurate account of historical events, but it’s a choice with consequences (even if often without obvious dramatic rationale). Why? Because the Hollywood version is not only the most vivid account we’re likely to see, but for many of us it’s the only one. Even if you know that Hollywood fictionalizes its stories, the movie version, with its detail and immediacy, will still likely be your dominant frame of reference. And the better the movie, more so.

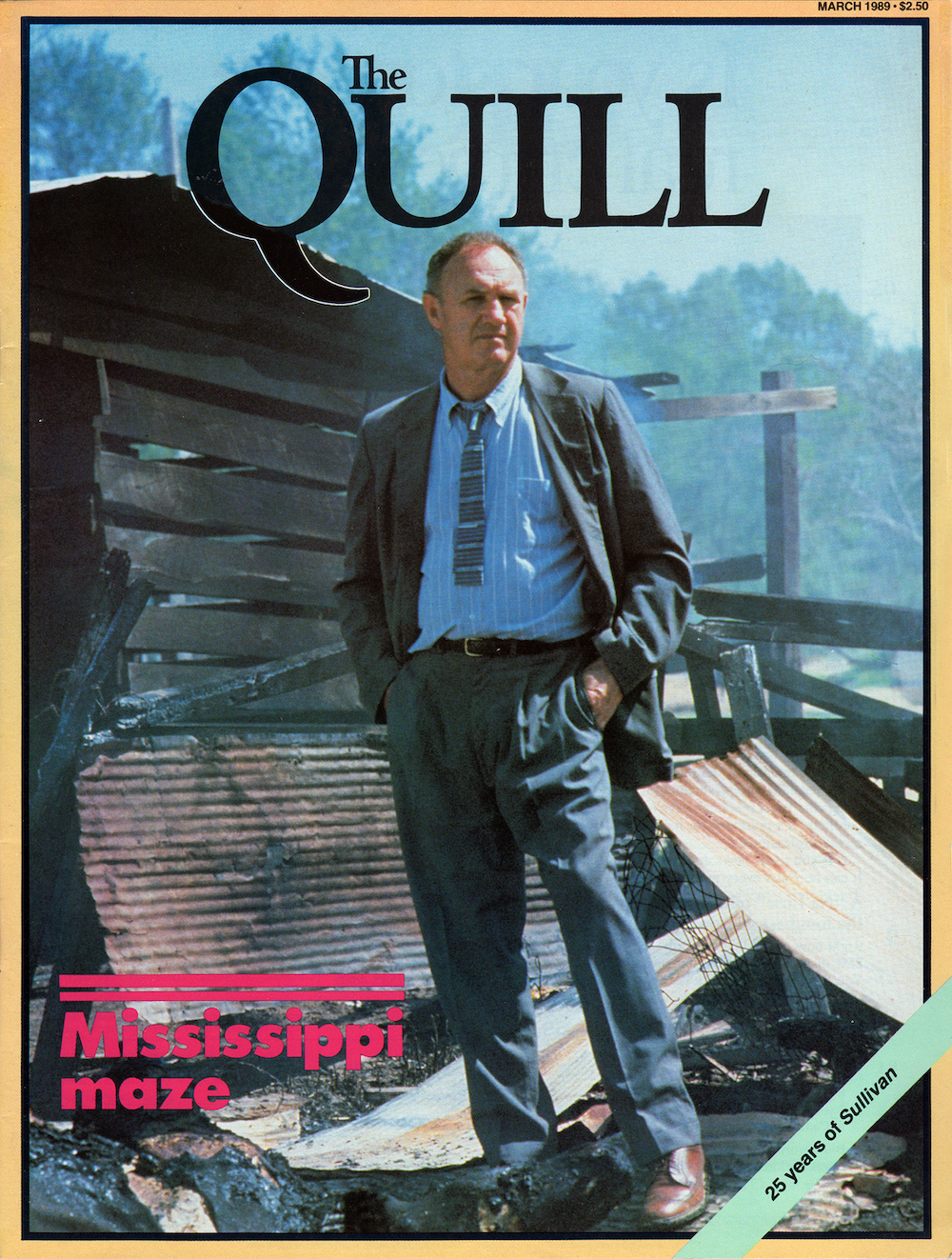

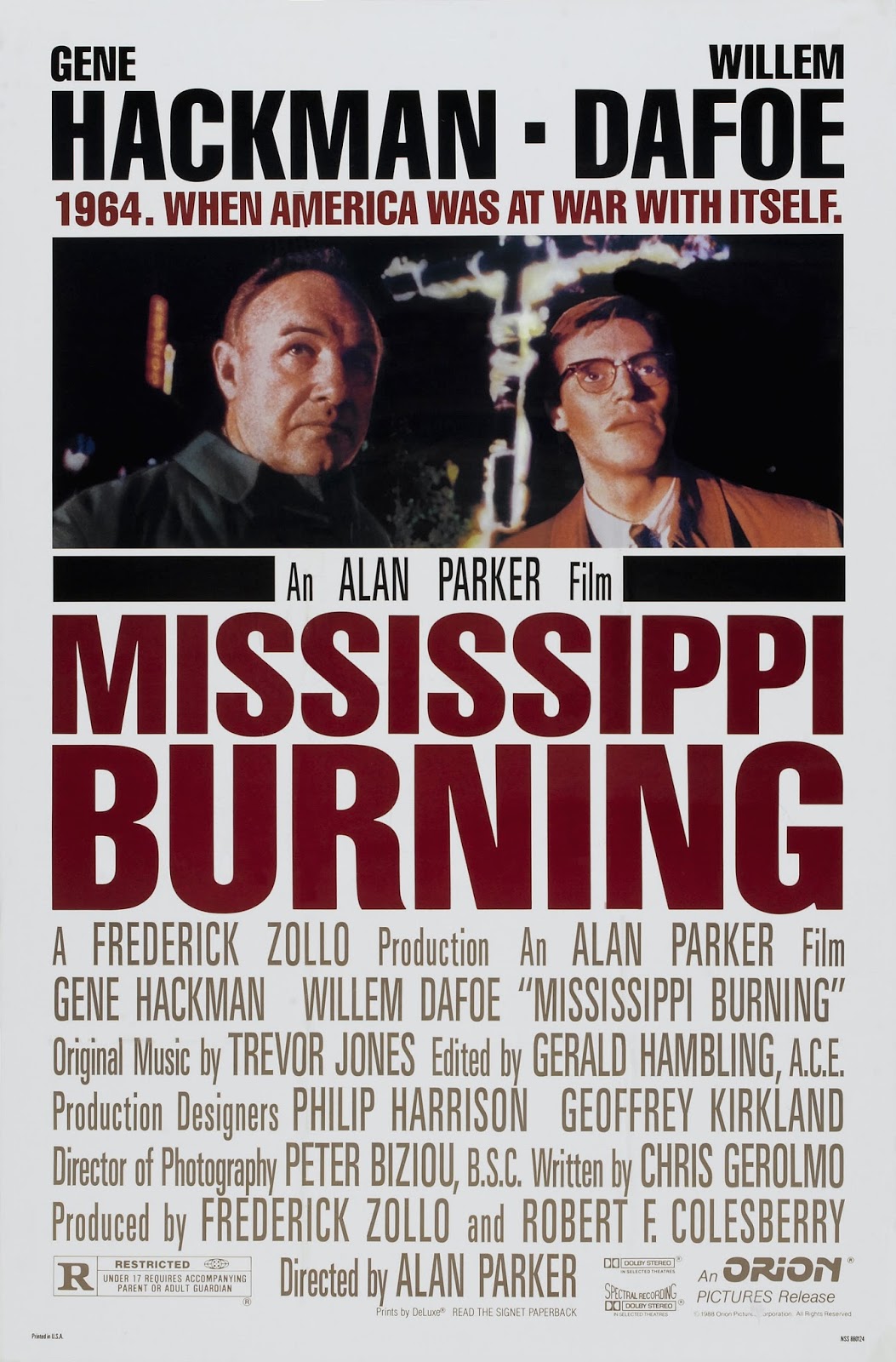

This piece was prompted by the Alan Parker film Mississippi Burning, starring Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe. It appeared in the March 1989 issue of The Quill, a journalism trade magazine published by the Society of Professional Journalists.

Mississippi morass

When Hollywood messes with history, everyone stands to lose

Imagine the film version of All the President’s Men, but with a few kinks, wrinkles, and twists.

“Forget Woodward, Bernstein, Ervin, and Cox,” the producer says at a pre-production meeting. “Journalists and old folks aren’t sexy enough. I want to get people wrapped up in this story. I want them to cheer when Nixon gets his.”

To sell such a serious, sensitive subject to a mass audience, the film version will have to make a few alterations to the actual history of the scandal.

“How about an action movie?” asks the assistant producer. “Let’s play two cops off each other — an idealistic, by-the-book rookie and a hardened veteran who knows how to get things done.”

“Sure,” says the producer. “Corruption in high places. The rich, the famous, the powerful, and two crack FBI agents plowing through it all.”

Watergate is finally broken wide open in the film when, after first pursuing the investigation by the book, the two detectives realize just how rotten the administration is and decide to get down and dirty to match it. The veteran agent gets a Cambodian G-man to kidnap Henry Kissinger. While suggestively fondling a canister of napalm, the mysterious Cambodian, posing as a terrorist, demands that the secretary of state tell what he knows of the coverup, or risk learning the terrors of jellied gasoline firsthand.

Other agents impersonate journalists and grab John Dean, telling him that Haldeman and Ehrlichman have already talked and said that Watergate was Dean’s baby. Does Dean want to come clean now? Later, the older agent roughs up John Mitchell in the lobby of Mitchell’s apartment house. Knowing that the FBI will shortly nail him to the wall, the late attorney general tips off the agent that Nixon taped everything.

In the end, the whole lousy crew is sent to jail, Nixon resigns, Kissinger is disgraced, and another case has been rousingly broken by the FBI.

Omissions and Distortions

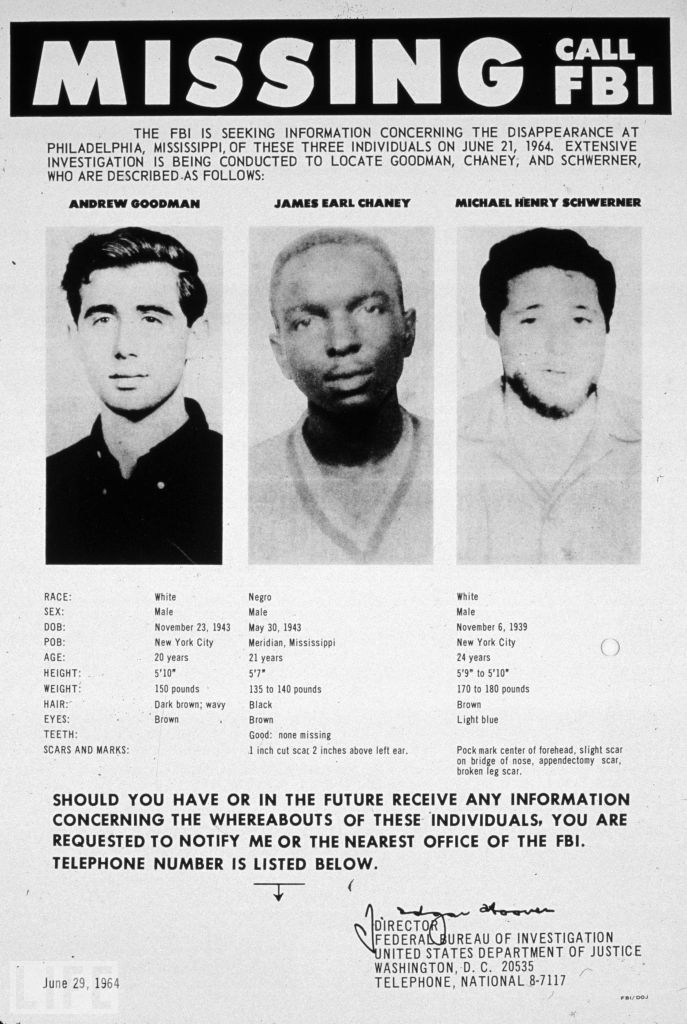

What the makers of Mississippi Burning did with the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner by members of the Ku Klux Klan is just a little less egregious than this mistelling of Watergate. It was the FBI that actually cracked the case, as Bill Minor points out on page 24. Otherwise, the film’s variance from the historical record is substantial.

Mississippi Burning has been praised by some for capturing the spirit of white Mississippi’s reaction to the civil rights movement and driving home the racist violence and the bigotry behind the murders. It is hard to leave the theater without feeling repelled by the brutality that ordinary white folks were willing to use to defend a racist way of life they could not conceive of living without. Critics and audiences have responded to that message over the last two months, as well as to the film’s cinematic qualities. It has already won National Board of Review awards for best picture, best actor, and best supporting actress, and has been nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

But Burning also has been harshly criticized for its omissions and distortions. It underplays the Klan’s impressive organization, for example, as well as the breadth of official and therefore “respectable” fury at civil rights activists, as well as for anyone that helped them. The movie presents little of the context, much less the content, of the civil rights movement, which was intimately involved in the events in Mississippi and in the murders’ aftermath that summer.

Blacks are presented mostly as a background canvas upon which the actions of the white protagonists are portrayed. Nor does the film give much sense of the national dimension of the case, which, aside from the headlines it generated, included the direct involvement of President Johnson and Martin Luther King.

The sharpest criticism has been reserved for Mississippi Burning’s representation of the FBI. To cast two of Hoover’s agents as the heroes in a civil rights drama based on real events is hard for many who lived through the era to swallow. It was J. Edgar himself, after all, who oversaw the harassment of Martin Luther King. Before the three civil rights workers were killed, Hoover had publicly stated that the FBI would not “wet nurse” the students in Mississippi. The bureau was pushed by President Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy, and other federal officials into a major commitment to solve the Mississippi case.

The agents who broke the case deserve credit for their work, but telling the story from their point of view puts an odd spin on it indeed. And those agents, whatever one’s feelings about the FBI, didn’t use anything like the violent tactics the film portrays when they got aggressive in their investigation of the civil rights murders. The real mayor of Philadelphia, Mississippi, was not threatened with castration by an FBI operative. Agents did not stage a lynching party. The course of the probe was not determined by the interaction of an earnest, by-the-book young idealist with a solve-it-anyway-you-can older agent — a dynamic that owes more to television’s Adam 12 than to the 1964 “Mississippi Freedom Summer.”

0ur fantastical revision of All the President’s Men presumably would not get past the first rewrite. It clearly is on the too-far side of far-fetched. Mississippi Burning, though, with its glib rewriting of history to fit the conventions of a police thriller, is playing to large audiences around the country. At the end of the long roll of credits that conclude the film comes a disclaimer: “This film was inspired by actual events which took place in the South during the 1960s. The characters, however, are fictitious and do not depict real people either living or dead.” Movie disclaimers are routine legalisms; one would not want to make a film about modern events without one.

This disclaimer is particularly disingenuous, though. The makers of Mississippi Burning didn’t just take a random slice out of Deep South life to provide background for their plot. They drew in careful — if reshaped — detail from the record of the murders and their aftermath. They built their narrative on events that remain charged with meaning, and which have been exhaustively documented.

More Important Than The Movies

“True life, and death, are so much more important than the movies,” director Alan Parker wrote in his Mississippi Burning production notes. “Hopefully, one day someone will also make a film about the importance of these young men’s lives.”

Parker was willing to scout 300 locations to find a small southern town that retained the feeling of a Mississippi county seat in the early 1960s. He meticulously recreated numerous scenes from news accounts, films, and photographs of the actual events. His efforts paid off in the realistic look of the movie, if not the plot. Similar efforts were not applied toward respecting the integrity of the history he was using as a backdrop. This raises the obvious question: When, if ever, does a historical event become sufficiently important to deserve accurate treatment in the movies? How historically accurate should a historically based movie be?

“The same question should be addressed to all people who are in the process of telling stories, who are in the process of reinterpreting historical events from different perspectives,” Michael Marsden, editor of The Journal of Popular Film and Television and professor of popular culture at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, told The QUILL. “To assume that historians are not fictionalizers or story tellers is also a mistake.”

Adds John Nachbar, Marsden’s co-editor at the journal and also a professor of popular culture at Bowling Green State: “It’s impossible to write history without interpreting it. Otherwise you will have nothing more than a list.”

Filmmakers clearly operate under a broader view of the truth than historians, or journalists for that matter. Movies as artistic narratives typically adhere to an internal standard of truth. Their goal is to be complete and to make sense within themselves. Reporters, by contrast, are constantly checking their perceptions of the truth against the external reality of events and the expertise of others. These procedures make a difference. As rare as it is for all journalistic accounts of an event to agree on exactly what happened, a news story is still likely to represent the facts more fully and accurately than a dramatization.

Yet that does not mean a film says nothing of the history it portrays. Indeed, a film version can make the meaning of a historical event emotionally compelling in a way that a straight news story, or a historian’s retelling, often cannot. “

It seems to me if you want to get at the essence of an event, a filmmaker can make as many claims to the essential truth as the historian can,” Nachbar says.

Film pioneer D.W. Griffith believed the public eventually would be learning most of its history from movies, according to John O’Connor, professor of history at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark and editor of the journal Film & History. Griffith thought “people would be, in effect, experiencing the past events and be able to judge for themselves.”

For better or worse, Griffith’s vision may not have been that far from reality [which makes his racist epic Birth of a Nation that much more appalling]. It is an old refrain by now, but popular culture does matter, more so than a great deal of what is officially stamped “important” or “educational.”

As writer Dick Hebdige wrote recently in the British weekly New Statesman & Society, “In the West popular culture is no longer marginal…. Most of the time and for most people it simply is culture. All the rest is hobbies: visiting museums, stamp collecting, pigeon fancying … reading nuclear physics, Karl Marx, Gertrude Stein, or Wittgenstein.”

Acquiring a knowledge of history could be added to the list of hobbies, and it is a not an especially popular one, which makes the history that gets communicated in movies that much more important.

Marsden cautions that there is little empirical data on just what audiences do with the information they take away from a movie.

Don’t Expect To See History

“A lot of the people who go to see movies don’t expect to see history,” he says, noting that audiences are diverse and will interpret films in different ways. The problem may not be “that they walk away with the wrong information, but with no information,” he said.

It still seems reasonable to suppose, though, that movies are a major source of information for many people. In a media-drenched world where people “know about” many more events than those they have experienced directly, it is the movie or TV program or the news report, not the actual event, that is likely to affect their consciousness, their values, and their understanding.

“I think if you said to them, ‘Is this [film] an exact reproduction of history?’ I think most of them would say ‘No.’ But this is the closest thing maybe many of them have,” Nachbar points out.

When a movie or TV show turns its scrutiny to a historical event, it is doing more than just drawing out broad meanings or gathering raw material for an entertainment. The movie depiction of the event is likely to represent for most people the polished and finished version of the journalist’s rough first draft of history.

“If asked directly, people recognize that the movies are concoctions, that they’re representations,” O’Connor says. “But saying that when asked and feeling that when you’re in front of the big screen and being taken away by something that tens of millions of dollars has been spent on to make it flawless, to make it feel that you’re being taken back into the past, are two different things.”

Assume for a moment that for millions of people the version of events in Mississippi Burning will be the last word on the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, and on the whole bitter, intensely significant conflict between segregation and the civil rights movement in the 1960s. That would make Mississippi Burning news. Because of the film, the events of the early and mid-’60s have once again entered the public’s consciousness, and these events are themselves still worth writing about.

Journalists might ask about what is historically accurate in the film, for example, and what are the gaps they can try to fill. They can ask how the murders could have happened, about how they tie into the history of the South. And why did the three civil rights workers die? Did their deaths accomplish anything? How do they fit into our understanding of the 1960s? Would change have come to the South anyway, and more easily, had they and others like them stayed home, where they could have addressed Northern racism? How has Mississippi changed? How has the status of blacks changed? What about the meaning that Mississippi Burning is communicating to its audience? Are viewers treating it as only a cop movie and forgetting the history? How do they feel afterward about the South, civil rights, and the FBI?

Consigning a film like Mississippi Burning to the movie pages for advice as to whether it is a good and entertaining film misses the point, not to mention the story. Movies are typically compartmentalized as entertainment, which is all most of them deserve. But even serious movies, such as Burning, are seldom treated as news in themselves, or as opportunities for education.

To be sure, some news organizations have picked up on the news implications of Mississippi Burning. The New York Times, ABC’s Nightline, and Time magazine, among others, have treated the movie as a legitimate news event. The Times has covered it extensively, including a pair of counterpoint stories in its Sunday arts section on January 8, an op-ed piece on the film January 14, and a reaction story from Mississippi on January 15. Nightline devoted a program to the controversy, featuring a discussion with Gene Hackman, whose performance in the film may win him an Oscar, and with Julian Bond, the former Georgia legislator who was a founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Time’s January 9 cover story on the film, written principally by film critic Richard Corliss, examined the controversy over the movie in some detail. Among other things, the article considered how Hollywood has dealt with race in recent decades and how movie makers capture and recast reality. The spread included a sidebar delving into Burning’s historical lapses.

A Larger Truth

That the film has sparked discussion of underlying issues is to its credit, even if critics like Julian Bond find its glorification of the FBI and short-shrifting of blacks repugnant, and even if the filmmakers are nettled by second-guessing criticisms they probably find petty and irrelevant. (The filmmakers themselves were unavailable for QUILL interviews during the preparation of this story.) The defenders of Mississippi Burning say the film’s variances from the historical record can be excused as necessary to getting at a larger truth. “You don’t go in a movie theater expecting to see and hear facts. The best you can hope for is a sense of reality,” Mike Royko wrote in his January 18 Chicago Tribune column praising the film. “It shows the South as it was in 1964. And for those who weren’t around 25 years ago, or were too young or distracted to notice, the film can be educational.”

Movies do portray a less tangible reality than that which can be gleaned from newspaper clippings and TV footage — any good film has to capture an impression, a spirit, a meaning that transcends its details.

“In some ways it’s an easy out to ask ‘Was it accurate or wasn’t it?'” O’Connor says. “What’s more important than technical accuracy, since the movie has to be a representation anyway, is the way in which the film elucidates the historical issues that are important…. The idea is … to get a point of view that is generous, that is based on research, that is not thoughtlessly biased … but still to recognize that it is a point of view, hopefully a … thoughtful or scholarly based point of view.”

Yet even knowing that a film is an interpretation, a work of fiction, it is easy for at least some portion of it to slip into the viewer’s consciousness as factual, especially when the viewer knows little about an event or person. At least some of the “facts” that many people think they know about William Randolph Hearst are really the truth only of Orson Welles’ Charles Foster Kane. Unless they know the real history of Hearst, they are likely to have a hard time separating the actual man from Citizen Kane. The film may indeed have left its audience with a better sense of what Hearst was about than a documentary-style version of his life would have, but its “facts” remain simply wrong.

The misinformation Hollywood spreads can matter. Consider the idyllic portrayal of the “facts” of slave society in movies such as Gone With The Wind — “facts” that are communicated as much in the atmosphere, the general feeling of the movie, as in the events it portrays. Then there is Hollywood’s role in falsifying the real-life confrontation between white men and America’s Indians. Several decades of wildly inaccurate — if highly entertaining — movies helped justify and cover up this country’s systematic program of genocide against its native people — easily one of the most important parts of America’s past.

Similarly, D.W. Griffith’s falsifications in praise of the Ku Klux Klan in Birth of a Nation are hardly innocent. (According to William Bradford Huie’s 3 Lives for Mississippi, which was used as a source for Mississippi Burning, “more than half” of the men who murdered the civil rights workers had seen Birth of a Nation within the preceding 12 months.) If you want to see the Klan for what it is, if you want to know the facts about Hearst, about slavery, if you want to know what really happened in the West, you would be better off reading books. There you would have at least a chance of getting at some hard historical facts amid the points of view and other unavoidable distortions and lacunas of the historian’s craft. Don’t bother with the movies.

Meanings And Facts

Whatever the point of view, whatever the larger meanings, is it necessary to do violence to the facts to get people to flock to the theater? And isn’t there some causal connection between those larger meanings and the facts from which they are drawn? The hackneyed plot devices of police thrillers are not the only tools for making a movie exciting and successful. There are different ways to massage the facts, to fill gaps, to insert ellipses, to present a point of view, than introducing fabrications. That just happens to be the favored method in Hollywood, but that in turn means it is not entirely fair to single out Mississippi Burning for criticism. It comes only a year or so, for example, after Brian DePalma’s The Untouchables, whose old cop-young cop dynamic between Sean Connery and Kevin Costner was virtually replayed in Burning between Hackman and Willem Dafoe. Both films recast history in almost comic-book terms with their black-and-white views of the world.

It is easy to say that such recasting is necessary, that historical events don’t become real for people until they have been simplified and dramatized. And it still seems fair to ask whether the meaning of a film like The Untouchables or Mississippi Burning is in some way diminished by the fact that its makers did not come to grips with history. Certainly every instance of truth that is removed from a narrative is a lost opportunity to reveal something more of reality to people who need to know.

While it may be an act of sophistication and humility to understand that we can never achieve a pristine truth in our communication, it is frightening to imagine what future students of our time will say when they review the vivid account of ourselves in the endless hours of films, TV shows, and musical recordings we produce. What passes for history would likely be pretty embarrassing if a 20th-century American were to be around to try and explain the gulf between our account of ourselves and what really happened.

A comic book version of reality may be better than none at all. But does it serve our culture if that is the extent of Hollywood’s ambition?

“They’re only under one mandate, and that’s to make money,” Marsden says of movie people. “If they didn’t play fast and loose with some of the historical events, they wouldn’t be [making] interesting films.”

Filmmakers obviously do not have the same obligation to “the facts” that journalists or historians have. But while journalistic pretense to objectivity and absolute factualness can occasionally annoy, surely it is better than casual untruth, or knowingly misleading an audience. There is something to be said for at least trying to get at reality and its meaning, however dense the fog that envelops it. Filmmakers command enormous resources and influence, which can be taken to imply a responsibility to behave as artists, just as news scribblers are presumed to have a responsibility to act like journalists. Whether artists have some responsibility to the truth, even if it is a personal version, may be controversial in some circles, but what they do still matters to a lot of people.

“The question,” says Marsden, “is not whether films have a right whether or not to interpret or recreate history, but whether in the process they are destroying some truths about people and culture.”

Retreating behind an it’s-just-entertainment argument seems more like an act of evasion than of hard-headed realism. Unless they are mired in a hopeless cynicism, it seems fair to say that filmmakers have some responsibility for what they communicate. And part of that responsibility may be that the reality of history is worth attending to, especially when for many people movies are its only source. It is not that movies must all be documentaries or have serious pedagogical purposes — quite the contrary. But when films are dealing with serious subjects, they probably should take them seriously.

There is a point in the process of dramatizing real events and real people at which films are exploiting and misrepresenting them rather than drawing out their meaning. Does Mississippi Burning reach that point? If it does, its success with audiences and critics suggests that many of the people who go to see movies, like many of the people who make them, don’t care.

As our Watergate musings were intended to show, however, there is a line past which the recasting of history becomes too outrageous even for Hollywood. Maybe the press should be involved in drawing that line, or at least in suggesting where filmmakers (and audiences) might find it.

“Most people jump to how can we make the movies be more truthful, whatever that means. That’s a losing battle,” O’Connor says. Hollywood is unlikely to change, and a frontal assault to reform it could quickly raise free-speech issues. “The change I’d like to see happen,” he says, “is not to pressure the movie industry to do anything differently, but rather to sensitize students, and through them families, and through them the society at large, to be more critical viewers of everything they see.”

This is a process in which the press, by treating movies such as Mississippi Burning as more than objects of entertainment or excuses for celebrity fluff, could play a major role. The alternative is to turn over the cultural playing field to the crudest dictates of the box office, which means largely giving up on communicating historical truth to a mass audience. And the communication of historical truths is something journalists are supposed to have a commitment to, even if Hollywood doesn’t.

2020 Postscript

A number of journalists in 1989 were doing exactly what this article recommended: taking Mississippi Burning to task for its departures from the truth, especially its glorification of the FBI. Were it released now, its appropriation and distortion of one of the key events of the civil rights movement would make for a more intense firestorm..

Even a film that sparks no controversy in its own time can incubate outrage years later as standards change and blind spots become more acutely visible. It’s hard to know which works of art will remain palatable to future generations whose particular sensitivities aren’t entirely predictable — no creation will age perfectly. But a respect for history, an underlying commitment to telling truth, can provide at least some defensibility for the elisions, inventions and misinterpretations inevitable in any narrative.

That defensibility could even have monetary value, which is what dominates Hollywood decision-making, after all. Consider the way race, Hollywood’s most abhorrent blind spot, has diminished the worth of many studio efforts, from one-time classics like Gone With The Wind to the innumerable comedies where shuffling, eye-popping caricatures were routinely relied on to provide cheap yucks.

Of course, the stereotypes visible in otherwise estimable films were less about ersatz history and more about a racism so systemic that its frequent movie appearances were egregiously casual (and sometimes still are). But it’s a similar phenomenon. If your attitude to the truth is fundamentally cavalier, it should be no surprise when you don’t do much better with standards of ethics and, ultimately, human decency..

Read about a different kind of ersatz history.

Go to Quill Magazine.