E.T. Wickham: A Dream Unguarded, Clarksville, Tenn., Customs House Museum & Cultural Center, 2001. Softbound, 9 x 9 inches, 108 pages, 99 color photographs, 21 B/W photographs. Foreword by Ned Crouch, essays by Michael Hall, Daniel C. Prince, Susan W. Knowles, Janelle Strandberg Aieta, Ned Crouch and Robert Cogswell, bibliography. Photographic essays by Clark Thomas and Carol Turrentine.

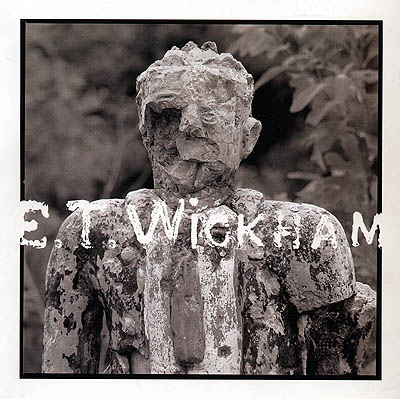

The fate of E.T. Wickham’s historical sculpture park in north central Palmyra, Tennessee, is one of the tragedies of 20th Century folk art. Thirty years of vandalism since his death have left headless bodies where there aren’t stumps and bare plinths where even the stumps have disappeared.

The beauty may be different from what the artist intended, but the site is still stunning: Desolation adds a sorrowful eloquence, especially in a country that isn’t littered with millennia of well-preserved ruins to contemplate.

As tragic as the destruction is the sparse recognition Wickham’s statues have received relative to other art environments, such as Fred Smith’s Concrete Park in Wisconsin or Eddie Owens Martin’s Pasaquan in Georgia. Now the Customs House Museum in Clarksville, across the river from the Wickham property, has helped close that gap with a major exhibition, catalog and symposium. It is encouraging to see a local, non-specialist institution embrace this environment, and the catalog, E.T. Wickham: A Dream Unguarded, supplies badly needed documentation of the site in its prime as well as its years of decay.

Born in 1883, Wickham, began creating sculpture with historical themes in the early 1950s. He erected near-life-size concrete figures that include the revolutionary patriot Patrick Henry, the Mafia nemesis Sen. Estes Kefauver, World War I hero Sgt.Alvin York, American Indian leader Tecumseh and the martyred Kennedies, along with sculptures of himself and family members. He also made statues of the Virgin and the crucifixion, reflecting his Roman Catholic conversion. The religious sculptures, across the road from his historical pieces, were less visible to the public and, for that reason, are better preserved.

Wickham, a farmer, had points to make about the history of the nation and the region, and he did not stint on inscriptions that laid out his ideas. “It is all over with now Bill and well that it is as it is,” reads one of the more succinct wordings, which concerned the Civil War. Partly because of those messages, the work seems more transparent in intent and, thus, more conventional than the art of Smith, Martin, Simon Rodia and other great environment builders. The roadside lineup of monuments resonates less with Rodia’s Watts Towers than with the Civil War shrines that are ranked along the highway in Georgia’s Chickamauga Battlefield. Wickham’s aesthetic seems similarly conservative, aiming more at naturalistic memorialism than at fanciful solutions to sculptural problems of expression and representation.

Still, it remains highly idiosyncratic for an individual without training or known artistic aspirations to create such an ambitious personal statement, and the overall presence of Wickham’s art is hardly less affecting than that of other important environments.

The Wickham catalogue documents that effect through a compelling selection of photographs. Pictures of the intact environment reveal Wickham’s artistic talent in a form that could never be understood from the ruins, while sumptuous images from photographers Clark Thomas and Carol Turrentine show the sculptures through the course of their prolonged destruction. The poignant images are an object lesson in the value of recognizing sites like this and taking early steps to preserve them.

Daniel Prince provides the catalogue’s editorial keynote with an essay that attempts to put Wickham’s work in context with other folk environments. Though Prince’s discussion ranges widely, he offers more generalizations than insights. There is actually more substance in the brief essays that fill in biographical and construction details and describe each statue. The book would have been even more useful had it documented the fate of all the statues (not just some), recorded the full texts of Wickham’s inscriptions, included current pictures of the site and showed the detailed scale model prepared for the exhibit. On balance, though, this catalogue is a major publication that belongs in the library of anyone interested in art environments.

A version of this review originally appeared in The Messenger, magazine of the Folk Art Society of America.

Here are photos of the 2001 Wickham exhibit at the Customs House Museum in Clarksville, Tennessee, and a page with beautiful original photos by Clark Thomas from the 1970s, some of which were used in the exhibit’s catalog.

Click here for my images the Wickham’s ravaged stone park, taken in 2019 and in the mid-1990s.