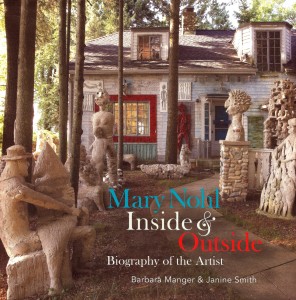

Mary Nohl Inside & Outside: Biography of the Artist, by Barbara Manger and Janine Smith. University of Wisconsin Press, 134 pages, 165 color images, 145 b/w or sepia images, 2009. ISBN 978-0-6152-5118-9. Soft Cover $29.95.

See my Mary Nohl photos, circa 1990

The first time I saw Mary Nohl’s masterpiece of a home and yard I only knew I was being taken to “The Witch’s House.”

That was its name for a generation of neighborhood kids, including the two who were showing me the one big curiosity in Fox Point, Wisconsin.

The reason for the visit was Nohl’s eccentricity, which made her yard a target for vandals as well as a local landmark. But it didn’t take long to see that the art was far more important than the oddity. I had visited a couple of art environments at that time, including Howard Finster’s Paradise Garden near Summerville, Georgia, and Nohl’s place was clearly one of those. It may have seemed more domestic than heroic, tucked away next to Lake Michigan in its comfortable corner of suburban Milwaukee, but it constituted a clear statement of her personal vision.

Over the course of four decades Nohl filled her wooded lot with dozens of concrete statues and wooden sculptures, and she trimmed her house with figurative reliefs and cutouts. This book describes the evolution of the environment step by step, along with a detailed account of Nohl’s life. Fortunately for both biographers and readers, she left plenty of material – diaries, letters, articles and more. Like her string-saver father, she tended to keep everything, including her large body of artwork, for Nohl was a prolific creator over and above what she put in her yard.

Photographs of the home’s interior show a fantasyland of wire constructions, soft sculptures, woodcarvings, paintings, ceramics and more. The pictures in this admirable book demonstrate a creative range that the exterior environment only hints at. The more work you see, the more you realize that Nohl’s was truly a life in art.

That life included formal training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago followed by several years teaching art in public schools in Maryland and Milwaukee. (Of those teaching years, Nohl concluded, “Teaching is the penalty I have to pay until I get original.”)

The independent means her parents were able to provide meant she could indeed spend most of her life being original rather than supervising classrooms. Backed by her father, she left teaching and opened a commercial pottery, turning out both functional and purely artistic ceramics. As with most such ventures, success was limited. By 1954, the business was closed, but while the pottery may have been a commercial failure, it produced a compelling corpus of ceramic work.

Nohl’s drive to create was hardly undermined by her commercial disappointment. Over the next decades her talent blossomed across multiple media – with the outdoor environmental sculptures at one end of the scale and jewelry at the other, along with thousands of drawings and paintings. (Interestingly, Nohl struggled with painting. Never satisfied, she would return to her canvases over the years to rework the paintings; at her death they were all still works in progress.)

The environment was equally long in the making, with Nohl beginning to imagine it while her mother was still alive, in the early 1950s. Her ideas for transforming the house and its yard were restrained by her mother’s disapproval, though Nohl began sneaking works into the yard while she was still alive. However, her mother, the last of her immediate relations, was dead by the time Nohl turned 50 in 1964. That left four decades for her to exercise her creativity restrained by very little other than her own sensibilities.

It’s that unfettered and obsessive creativity that arguably links Nohl with the great outsider monument makers. One of the most interesting possible affinities is with Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, the prolific artistic genius from the other end of Milwaukee. Von Bruenchenhein was slightly older, lived on a much lower socio-economic scale and shared his life with a wife. (Nohl never married.) And where Von Bruenchenhein, the self-taught baker cranking out visions of apocalyptic genius, can be taken to represent an Art Brut ideal, Nohl was cosmopolitan and well-trained, producing work that doesn’t seem so herculean in effort, even if it is hardly less hermetic.

But if we focus on the art, not the address or biography, it’s clear that both of them had an acute sense of themselves as artists despite their lack of recognition. Both seemed to create their own conceptual world as they built out visually intense interior spaces in their homes. Both spread their creativity almost willy-nilly across a wide variety of mediums. Both lived lives characterized by a degree of isolation that is hard to separate from their endless outpouring of work. The fact that each made sculpture from chicken bones is a bonus kinship.

Although Nohl said she “did not like art history and had no interest in reading it,” she not surprisingly disliked being called “naVve,” as Von Bruenchenhein undoubtedly would have as well. On the other hand, according to Manger and Smith, she tolerated the “witch” label that neighbors gave her, even if the resulting vandalism of her property became a daily ordeal. Each morning she checked for damage, and the countermeasures she took only increased the air of peculiarity around her home.

As with many art brut creators, it’s hard to separate Nohl’s artistic drive and extraordinary productivity from that isolation and the loneliness it implies. Yet by the evidence of this biography, her life, though not untroubled, was not unhappy. She traveled, had friends, and above all appeared to find true joy in her creative work.

She also knew the value of sharing that joy, providing for the work’s survival by willing it to the Kohler Foundation, which not coincidentally also played the key role in preserving Von Bruenchenhein’s legacy.

The continuing ambivalence of Nohl’s neighbors toward her environment means the property hasn’t been opened to the public, unlike like so many of the sites Kohler has preserved. But the art is protected, and through exhibits at the John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan and books like this one, it is finally reaching the wider audience that Nohl always deserved. And while the environment is a striking accomplishment, seeing the body of work from inside the house adds tremendous depth, with evocative images and striking stylistic devices recurring through the years. This book provides a fine record of that work as well as a sensitive account of what went into its making.

This review originally appeared in Folk Art Messenger, publication of the Folk Art Society of America.

There’s a feature film on the Fox Point Witch’s House currently in production! Check out the Facebook page for more information…

http://www.facebook.com/PilgrimageToTheWitchsHouse