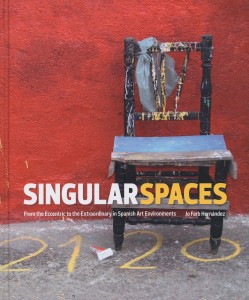

Jo Farb Hernandez’s study of Spanish art environments is so epic that even a large-format volume of nearly 600 pages can’t get the job done, so a bonus CD adds thousands more thumbnail pictures and hundreds more pages of text. If creating a world-class art environment requires obsessive devotion, Hernandez is a match for the creators she studies. Her devotion demonstrates Spain is a match for the rest of the world, even if its environments have not received the same attention as the great sites in France or Wisconsin.

Jo Farb Hernandez’s study of Spanish art environments is so epic that even a large-format volume of nearly 600 pages can’t get the job done, so a bonus CD adds thousands more thumbnail pictures and hundreds more pages of text. If creating a world-class art environment requires obsessive devotion, Hernandez is a match for the creators she studies. Her devotion demonstrates Spain is a match for the rest of the world, even if its environments have not received the same attention as the great sites in France or Wisconsin.

The country has no shortage of them. Fernandez relates how, after spending 10 years scouring the country and finding 44 sites, she discovered yet another one not five miles from her home.

By and large, those places are spectacular — some monumental in scale, some incredible in detail, most remarkable in conception. There are sites like Maximo Rojo’s Museum of History and Life in Alcolea Del Pinar, dense with statues telling the world’s history. Or monumentally eccentric buildings, like Jacinto Garcia’s multi-storied, elaborately decorated medievalist castle near Barcelona. Or the park-like educational environment built by Juan Maria Garcia Naveira in Betanzos over the first decades of the 20th Century.

Among the most impressive of these sites is the Capricho De Cotrina, built by Francisco Gonzalez Gragera in Los Santos de Maimona. Its flowing shapes echo the organic forms of Antonio Gaudi across the peninsula in Barcelona, though the artist demurs. Besides claiming he hadn’t been to Barcelona to see the Catalan architect’s famous projects before he started building, he points out that “Gaudi is a world-renowned architect. How am I going to compare myself to that?”

The Gaudi influence, or not, would be a fruitful topic for further consideration, similar to the question of how, and how much, Father Paul Dobberstein’s Grotto of the Redemption in West Bend, Iowa, influenced Wisconsin’s many 20th Century grotto builders.

Gonzalez’s structure in any case is stunning not only in its architectural form, but in the many fine details that Hernandez’s photography documents (as it does for so many of these environments). Why did he build it? According to Hernandez, mostly because he wanted a distinctive country home. Although a number of his fellow creators built with more of an agenda in mind, delivering messages that were frequently historical or cultural, there is something telling in the motto Maximo Rojo inscribed in his environment: “I do what I do for love, and I do not need another reason.”

If “love” is a start, Hernandez points out an internal dynamic that can drive artists to go further: “Making things stimulates one to make more things; the successful completion of one sculpture tends to provoke the desire to make another, as one learns from past methodological mistakes and branches out with greater conceptual confidence as well as physical and technical prowess.”

Or, one might say, once you go over the top with one idea, why not go still further with another?

The question of motivation seems apropos when thinking about these heroic undertakings, even if intention can be a fraught concept. However much we know about an artist and their context, however many questions we ask them, their purposes can never be perfectly known, nor will they fully explain the significance or meaning of a work as it is experienced by its viewers. With self-taught artists there is a particularly problematic tradition of relying on poorly researched anecdotes to draw conclusions about the art and its creators’ motivation.

It is difficult to begin to understand these environments, though, or to fully appreciate their uniqueness, without understanding the history of their construction, including what led these men (and in this book they are all men) to begin these eccentric projects and keep them going even in the face of hardship. These works are rare enough that there has to be something highly unusual about their makers and some purpose that must be known to unlock at least a part of their meaning.

Case in point: Julio Basanta Lopez’s amalgamation of sculpture, both original and commercially produced, spread across three houses in Epila. Not only did his work output increase after the shooting death of a son, his figures also “became more menacing and alarming,” Hernandez reports, seeing a direct connection between the life event and the art. The visual evidence supports her; this is a crowded and disturbing place. Fortunately, perhaps, an out-of-the-way location makes it obscure even in its own town.

That obscurity is not an incidental detail. Although Hernandez describes a few communities that actually embraced the work of these artists, the common story is indifference and, often, active resistance from neighbors and government officials. There are interesting questions to be asked about what leads people to create environmental works that put their community standing at risk, and she provides many fascinating answers, even if none can be entirely sufficient to explain the phenomenon.

She concludes this extravagant book with the extravaganza of Josep Pujiula i Vila’s incredible environment in Argelaguer, whose travails with officialdom prompted her to become actively involved in its defense. Yet as with so many of these makers, Pujiula is inscrutably modest about his monumental creation. He “had no initial intent other than to entertain himself and occupy his free time,” Hernandez writes. “When you want to do something that pleases you, you always find the time to do it,” the artist says.

Working without a plan and with mostly found and cast-off materials, Pujiula built a vast array of wooden towers, mazes and other structures in an out-of-the-way location that, unfortunately, he didn’t own. Though the site became famous, the authorities repeatedly forced its demolition, and each time Pujiula stubbornly started building again nearby. The environment is truly unique, not only among the sites documented in this book, but among such sites across the world. And we have Hernandez to thank for giving it such thorough documentation.

There’s really nothing to bemoan in this book, except the curious lack of a general index and the persistent necessity for authors like Hernandez to recapitulate years of controversy about what to call the art, in particular the propriety of “outsider art.” That discussion might be interesting every once in a while, but its ubiquity is tiresome. At least her accounting is non-polemical, aiming at insights rather than scoring points against the alleged obfuscations of any given label.

In fact, she offers a decent explanation of what is distinctive about outsider art without embracing the term: “On a conceptual level the art environment builder’s connections may be more ad hoc, circumscribed, and personal simply because his/her frame of reference is such; many mainstream artists, in contrast, create work that links to broadly shared frames of reference, and particularly to preselected references reflecting the art world’s priorities, assumptions and education tracks.”

Hernandez thoughtfully places environments in an art-historical context while not losing sight of those individual factors. Indeed, the frame of reference for many of the artists she profiles is distinguished by the extent to which their deepest point of pride is in the triumph of making do, of creating something from nothing, rather than anything having to do with aesthetic achievement, let alone artistic intention.

Hernandez is not satisfied to take any of these intentions, or the artists’ own explanations, at face value. This is not a coffee-table book of superficial biography set amidst a smattering of pictures. Her years of fieldwork, documentary research and careful photo documentation are apparent on every page and in the way she brings both the artists and their work to life.

These sites display “an animated intensity that renders [them] resistant to single viewings and facile descriptions,” she writes. Fortunately, there is nothing facile about this book. It may actually be the most impressive single volume of research ever published in the field of self-taught art. At minimum, it can take pride of place next to important volumes such as Leslie Umberger’s Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds or the Bill Arnett-sponsored Souls Grown Deep books. And at a list price of $80, it is a remarkable bargain.

This review originally appeared in The Outsider, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.