Because Darger happens to be weird, however, this content in his work constitutes a symptom rather than a subject. It is MacGregor himself who writes that "The tendency to engage in clinical reductionism ... could have seriously obscured for the reader Darger's astonishing uniqueness as a personality and an artist." He obviously believes he resisted that tendency by waiting some 650 pages before discussing a literal diagnosis (autism, specifically Asperger's Syndrome). But reductionism is present throughout the book and explicit in his own statements: "All of these narrative-constructs, however objective they may initially appear, are reflective of subjective psychological content, shifting moods and elemental drives." Or put another way, "The flow of content in Darger is controlled, not by the logic of the narrative, but by internal necessity."

Because Darger happens to be weird, however, this content in his work constitutes a symptom rather than a subject. It is MacGregor himself who writes that "The tendency to engage in clinical reductionism ... could have seriously obscured for the reader Darger's astonishing uniqueness as a personality and an artist." He obviously believes he resisted that tendency by waiting some 650 pages before discussing a literal diagnosis (autism, specifically Asperger's Syndrome). But reductionism is present throughout the book and explicit in his own statements: "All of these narrative-constructs, however objective they may initially appear, are reflective of subjective psychological content, shifting moods and elemental drives." Or put another way, "The flow of content in Darger is controlled, not by the logic of the narrative, but by internal necessity."

Perhaps MacGregor was overwhelmed by Darger's massive work. The reader is "buried beneath an avalanche of overwhelmingly obsessive and oppressive detail," he writes. The reader of Henry Darger In the Realms of the Unreal may be forgiven a hint of the same feeling. It is testimony to the quality of MacGregor's scholarship that his reductionist psychology often contrasts with richer and more revealing insights about the man and his work. Despite that, and the pleasures afforded by the numerous reproductions, it is a chore to make it through this book. The lack of an effective editor is apparent from a text that is far too long and lazily argued to make its own case effectively.

An editor might also have toned down MacGregor's dubious hyperboles. References to uniqueness in the history of art and to the longest piece of imaginative prose ever written beg for rebuttal, since this book offers no proof that they are true. Yes Darger's output is singular, but so is any great work of art. And yes The Realms is long, but did MacGregor really survey world libraries and manuscript repositories before declaring it the longest ever (a claim already being repeated as fact by journalists whose highest authority is the first clipping they happen to see)? In the end the book reads something like a disillusioned spouse running through the flaws of their mate. You know there is a good deal of detailed truth underlying the claims, but you take the exaggerations and harsh judgments with a large grain of salt.

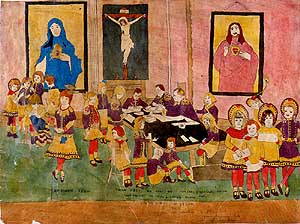

While this volume remains mandatory for anyone with a significant interest in Darger, those less ambitious have two good alternatives. Michael Bonesteel's book, reviewed previously in these pages, presents a more balanced if somewhat less detailed portrait of Darger and includes instructive extracts from The Realms, Darger's diary and other texts. Darger: The Henry Darger Collection at the American Folk Art Museum collects images from the museum's recently acquired authoritative Darger collection. Although some depict a mild level of violence, and nude little girls abound, the selection represents a relatively low-key cross-section of the work and includes a number of pictures not featured in the MacGregor book. An essay by Michel Thevoz mounts a brief but potent argument for why Darger matters, making this a decent starter package as well as a supplement to MacGregor's work.

A version of this review originally appeared in The Outsider magazine, published by Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.