I admit it. I love Nancy, and not ironically, at least not any longer.

I admit it. I love Nancy, and not ironically, at least not any longer.

I grew up reading Nancy and Sluggo every day in the Chicago Sun-Times, which says something about my parent’s household (i.e., the Sun-Times, not the Republican Tribune). But it was in college that I became truly devoted to Nancy and her creator, Ernie Bushmiller.

I arrived during the flowering of Doonesbury, which was making its always-witty points on doors and bulletin boards all over campus. I needed to take a stand. Coating my dorm-room door with Nancy comics, I staged my own protest and became an early member of the Secret Bushmiller Society before it existed, or before I knew it existed anyway.

Beside clipping and posting the daily cartoons, I also scratched Ernie’s name into lecture hall desks all over campus. It was my way of committing to a purer sort of art than the antithetical Doonesbury. To summarize:

• Doonesbury was hip, Nancy square.

• Doonesbury had messages, Nancy gags.

• Doonesbury was hippie, Nancy punk (proto punk, technically).

• Doonesbury was more or less representational, Nancy abstract

• Doonesbury’s characters were au courant, Nancy’s generations behind.

• Doonesbury was topical, Nancy timeless.

• Doonesbury was complicated, Nancy minimal.

Much of this was apparent to me at the time, though I also had a nagging feeling that at some level Nancy was lame and Doonesbury sophisticated. That’s what just about everyone thought.

Over the years my appreciation for Nancy deepened, however, even while my hostility to Doonesbury waned into indifference. Partly this reflected the development of my own aesthetic sensibility, unconsciously at first, and then explicitly under the Bushmiller influence. Also, I would occasionally stumble across others who shared appreciation for Nancy. Friends like Tom Recht, David Rubien and Bill DeBauche, and the occasional writer or artist whose public recognition of Bushmiller helped me better understand just why the strip was important. The first of these others was Tom Smucker, writing in the Village Voice in 1982. For example, “Bushmiller choreographed his familiar formal elements inside the tightest frame of any major strip, and that helped make it the most beautiful, as a whole, of any in the papers.”

Other voices of support came later, including the rise of the official, albeit elusive, Secret Bushmiller Society, courtesy of comic artist, publisher and impresario Denis Kitchen.

Other voices of support came later, including the rise of the official, albeit elusive, Secret Bushmiller Society, courtesy of comic artist, publisher and impresario Denis Kitchen.

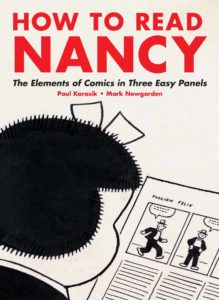

The comics publisher Fantagraphics has supplied the strongest validation, starting with its effort to reproduce the complete strips, currently at Volume 3, and now How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels.

Comic artists Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden try not just to glorify Nancy but to explain her. The book supplies breadth, with lots of biographical information, and depth, via an extended close reading of one representative strip and the myriad choices Bushmiller made to entertain his audience that day. Altogether they make a serious argument for Bushmiller and his creation.

They originally made this case in an essay included in Brian Walker’s ground-breaking 1988 volume, The Best of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy. The strip they chose to scrutinize, from Aug. 8, 1959, is not exceptional, but that’s the point. It’s typical of Bushmiller’s style, both visual and comedic. Now this book-length analysis lets them show in rich detail just how much creativity, care and brilliance went into crafting the perfectly balanced world that is Nancy’s ultimate triumph. While fans may start out loving her for gags even a five-year-old can understand (as Bushmiller worked consciously to supply), some of us end up committed to the flawless graphical precision that made Nancy and Sluggo the ultimate cartoon icons. The book’s analysis not coincidentally also gives insight into the nuances of cartoons more generally. What you learn reading Nancy also informs how you might read other comic art.

Nancy’s iconic status, especially within the art world, is something the authors survey in one of many appendices that provide pointedly learned background on this comic and its virtues. There are also plenty of additional strips included in this volume, well selected to demonstrate key Bushmiller themes, both comic and visual.

It all adds up to an authoritative, even credible, treatment of one of the cartoon giants of the 20th Century. Whether you love Nancy already or still just scratch your head, this book is worth reading.

Thoughts on Nancy circa 1995.

Denis Kitchen on the Secret Bushmiller Society.

I loved Nancy as a kid, too. My younger brother had Nancy and Sluggo rubber dolls. He wanted to bring them to school but our mother thought the boys would beat him up for it. How I wish we still had those dolls! Anyway, I’ve analyzed my infatuation with the Nancy strip and it’s much like another Nancy (Drew): It’s because there are no parents in the strip, not even their legs. That’s what we (I, at least) wanted in my childhood world: no parental interference.

Thanks for this excellent review.